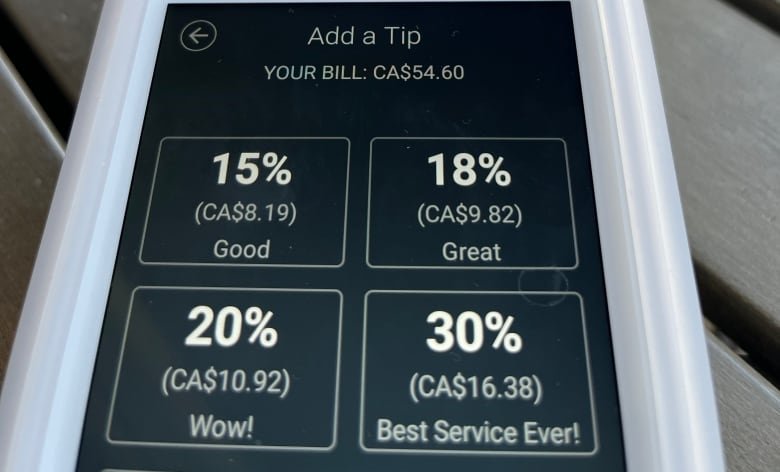

As credit card machines prompt customers to leave higher tips at all kinds of businesses, some workers say point-of-sale terminals are making it easier for employers to pocket their hard-earned cash.

Jackson Mundie, who used to work at a Montreal sandwich shop, says his boss swindled him and his colleagues out of hundreds of dollars in tips left through credit card machines last summer.

Quebec’s labour standards don’t restrict employers from asking their clients for tips.

Yet, Section 50 of the province’s labour code states that any “tip collected by the employer shall be remitted in full to the employee who rendered the service.”

Suspecting that his employer was withholding money, Mundie kept track of tips left electronically throughout his shift by noting transactions when he was operating the cash register.

“I definitely felt scammed,” Mundie said. “Most people would expect it to go to the employees that are directly serving you.”

Who is entitled to tips?

Quebec is the only province that has a different, lower minimum wage for workers who are expected to receive tips regularly. That salary has been $12.20 per hour — about $3 less than the province’s general minimum wage ($15.25) since May 1.

A spokesperson for the Labour Ministry said in an email that “tipping offers better equity between tipped employees and those receiving the general minimum wage.”

It is legal to pay an employee the tip wage rate if they work at a bar, in a train or on a ship where alcoholic drinks and food are sold or a business that offers tourist accommodation, like a campground. The rate can also apply to workers of a business that sells or delivers takeout meals.

But establishing who exactly is entitled to tips, regardless of their wage, remains unclear.

The CNESST, Quebec’s workplace safety board, enforces rules about working conditions. It says that in the last five years, it has dealt with on average 250 complaints annually related to the transfer or distribution of tips, according to documents obtained through an access-to-information request.

Anyone in Quebec can ask for tips but whether or not the tips have to be distributed by the employer is less clear.

In emails to CBC, spokespeople for CNESST and the Labour Ministry insist that it does not matter if an employee is paid the tip-wage rate or the higher minimum wage, their employers are required to transfer tip money to them — whether the sum is left in a jar or comes through a payment terminal.

“Obviously, the CNESST does not intervene in the choice of giving a tip or not, since it is at the discretion of the customers, regardless of the employee’s salary,” a spokesperson for the Labour Ministry said in a statement. “The CNESST says, however, that the entire tip must be given to the employee who provided the service.”

Under the wording of the law, Mundie should have received tips left by customers simply because they were intended for him. But when he filed a complaint to the CNESST, he was told that his position as a fast-food service worker made him ineligible to receive gratuities, much to his confusion.

CBC reviewed CNESST’s response, which stated that Mundie is “not considered as an employee who receives tips as per the definition of the labour law.”

At the shop, he cooked and packed food, cleaned the dining room and worked the cash register for $18 an hour, which is indeed above the wage for workers expected to receive tips regularly.

Knowing that customers had left tips for him, Mundie says businesses should be more transparent with clients about who will receive gratuities, especially because of no-contact payment.

“We were the ones putting in that labour so for my boss to solicit tips and then not give them to us is super unethical,” Mundie added.

Sean Blumer, who worked at another fast-food restaurant for five years at the general minimum wage, said he quit his job at the end of 2021 after he found out the owners were withholding tips from employees.

“It felt kind of like a stab in the back,” he said. “If someone tips you, they appreciate the service you’re doing. It’s their money that they don’t have to spend, that they’re choosing to give to you.”

Blumer says, now, whenever he tips, he prefers giving cash directly to the worker or leaving it in a tip jar.

Preset tip amounts pressure customers, expert says

Faced with inflation and a labour shortage, many businesses trying to keep their products at a competitive price and retain employees are suggesting higher tips, even for takeout services.

But proposing 25 to 30 per cent tips can backfire, says Marcelo Nepomuceno, an associate professor at HEC Montréal and the Canada Research Chair in Consumer Decision-Making.

He says nudging consumers at the counter is a risky attempt to change the social norm of tipping that pressures the service worker and the customer who, he says, aren’t in conflict.

“There is a lack of information on the consumer’s side,” he said. “Consumers don’t necessarily know who is getting what. The only thing that consumers know is the social norm.”

Nepomuceno said being aware that certain service workers receive the province’s minimum wage might make customers less likely to tip.

“They will feel that they are being exploited” because the social pressure of helping the employee earn minimum wage is no longer there, he said.